Bon appétit Ishikawa!/Sake Rice

Hyakumangoku-no-Shiro: developed over a period of 11 years. 2

Realizing the wish to “brew daiginjo sake using rice from Ishikawa”

Ishikawa Prefecture is blessed with an environment suited to sake brewing, such as cold winter climate and pure groundwater from the Hakusan mountain range. The prefecture boasts Noto master brewers, Japan’s representative master brewers, as well as 37 long-standing breweries. The local breweries and master brewers have waited earnestly for the development of Hyakumangoku-no-Shiro brewers’ rice. We visited the agricultural experiment station of Ishikawa Prefecture Agriculture and Forestry Research Center in Saida-machi, Kanazawa City. They told us that the breeding of Hyakumangoku-no-Shiro dates back to 2005.

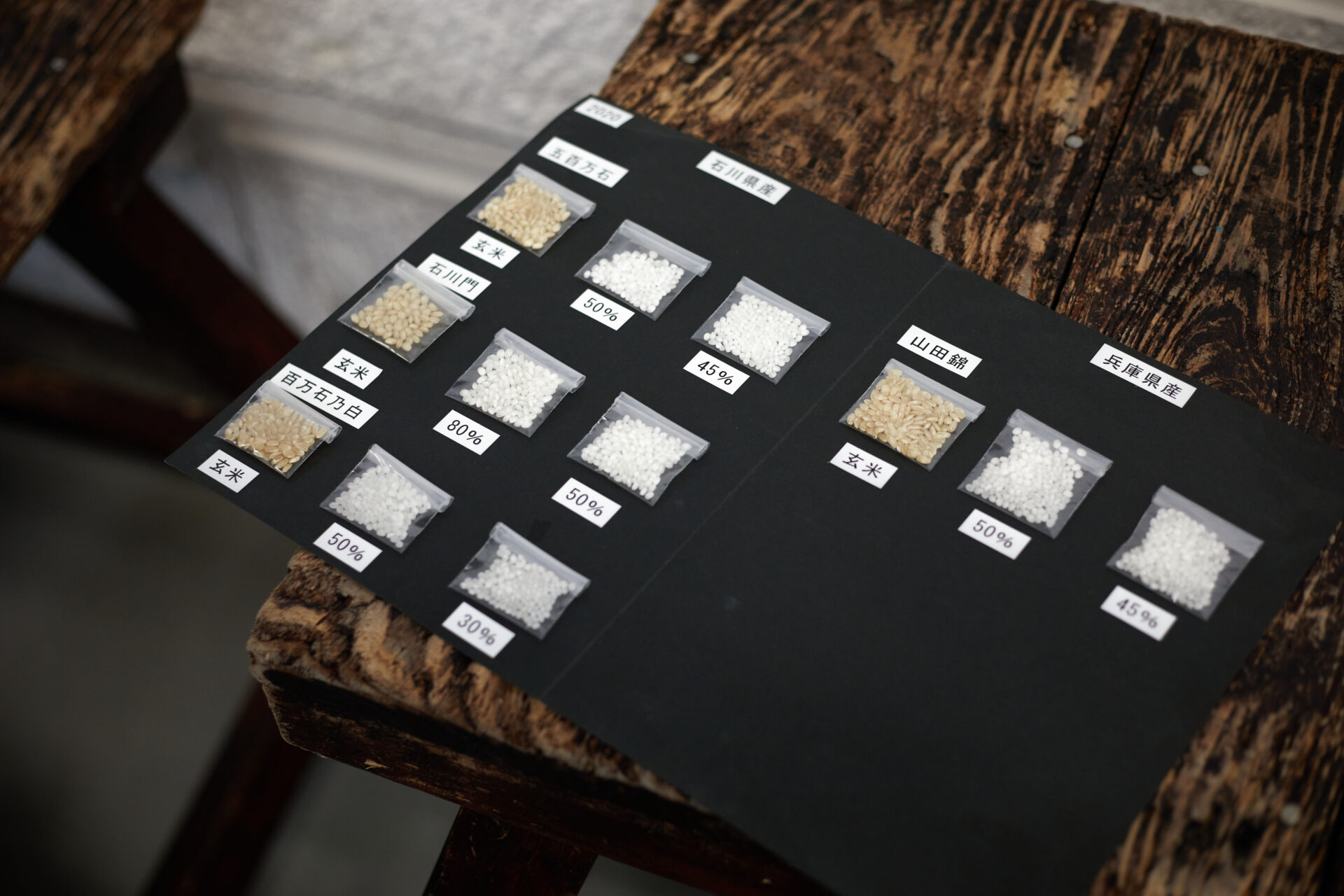

At that time, the consumption of Japanese sake was declining, and the breeding of a local brewers’ rice was being called for to produce sake with a local distinctiveness and added value. Most of the daiginjo sake in Ishikawa was produced using Yamada-nishiki from Hyogo Prefecture. To make daiginjo sake, the rice should be ground down to a volume of less than 50%. Yamada-nishiki is known as “the king of brewers’ rice” in the ginjo sake category, since its grains are large and not damaged easily during grinding. The development of the new breed began in order to meet a request from the Ishikawa Federation of Sake Breweries Associations, which was the wish to produce daiginjo sake using Ishikawa rice. The requirement was stated specifically: the rice should not be damaged after grinding to 50%.

Hakuei Hatanaka told us that they crossbreed 50 pairs of rice each year. “The core of a rice grain is very fragile; therefore, rice breaks easily after being ground down close to the core in order to make daiginjo sake. To solve this problem, we selected rice breeds with small cores for crossbreeding. After selecting promising combinations, we have to wait for a year to see the result. After we decide on several promising combinations, we need to perform experimental brewing and repeat the selection process, thus requiring a lot of time. Even when we obtained rice that was not damaged easily, we experienced other problems such as small harvests or poor sake tastes. In total, a period of 11 years was spent to develop Hyakumangoku-no-Shiro.”

“’05-sake 83” Ishikawa original brewers’ rice was developed by crossbreeding “Hitohana” large-grain rice and “Niigata-sake 72” daiginjo rice. It was further crossbred with Yamada-nishiki to produce the ideal “Ishikawa-sake 68” rice, which was later renamed Hyakumangoku-no-Shiro. The damage rate when grinding down to 50% was analyzed and found to be less than 10%, even lower than Yamada-nishiki’s 20%. It also exceeded Yamada-nishiki in harvest. The plant is 10% shorter than Yamada-nishiki; therefore, it is not easily damaged by typhoons and is also suited to cultivation in Ishikawa.

“To tell the truth, I cannot drink alcohol, so I can only check the sake using its smell. However, I was really glad when the others said that we produced a good sake during experimental brewing. I felt that finally we had developed a good rice to produce tasty sake.”

In 2018, 10 breweries in Ishikawa started using Hyakumangoku-no-Shiro; the number increased to 20 breweries in 2019 and 24 breweries in 2020. Many breweries are currently attempting brewing using Hyakumangoku-no-Shiro, and it is expected to become the main local brewers’ rice in the future.

The struggles in the rice paddies continue; searching for an appropriate cultivation method.

Rice farming has prospered on Kaga Plain since the olden days. Katsuhiro Hayashi cultivates rice, wheat and soybeans in Yamajima, Hakusan City, in the center of the plain. He is also actively engaged in growing brewers’ rice. In summer, the temperature drops significantly at night due to cool air carried by the Tedori River, which produces a large temperature difference between day and night, a favorable condition for the production of quality rice. Mr. Hayashi grows Gohyakumangoku, Japan’s 2nd-largest harvest volume rice after Yamada-nishiki, and Ishikawamon, a brewers’ rice from Ishikawa developed in advance for producing ginjo sake, and he also began growing Hyakumangoku-no-Shiro three years ago. He is the chairperson of the Hyakumangoku-no-Shiro Study Group established by the farmers in July 2020. This is the fourth year of production of Hyakumangoku-no-Shiro; he planted the rice in a 3.3 hectare field. He says he has gradually understood the breed’s characteristics.

“Hyakumangoku-no-Shiro’s stalks are very thick and they spread out as they grow. In the harvest season, the roots spread out widely. The harvest season is a month later than those of Ishikawamon and Gohyakumangoku; therefore, the grains are tightly packed. The ear shape is a little awkward; however, it makes the plant sturdy in strong winds, enabling large harvests.”

The 25 producers in the Hyakumangoku-no-Shiro Study Group exchange information about suitable cultivation methods and post-harvest management. Their current issues are the selection of fertilizer and fertilization timing. They aim to supply rice with consistent quality regardless of the production area and producers, and to establish a distribution system for stable supply.

Since rice is farmed only during summer, Mr. Hayashi experienced working as a brewer at Yoshida Brewery in winter; he wanted to learn about the place his rice was used. “We farmers are inclined to grow only what we want to grow; however, we need to change our attitude consciously. It is interesting to understand what is required and what kind of agriculture we should aim for, and then we should take on challenges based on these facts. Honestly speaking, growing a new breed of brewers’ rice is difficult from a financial perspective. However, I will do it because it’s fun.”

Pursuing the sake brewing skills unique to this area, using water and rice that can only be obtained here.

Yoshida Brewery has produced sake for 150 years in the rice farming area of the Tedori River fan, located close to the sacred Mt. Haku. They produce Tedorigawa Junmai Daiginjo using Hyakumangoku-no-Shiro, without the addition of water, which was highly evaluated by Motohiro Okoshi. We met Yasuyuki Yoshida, who became the seventh president of Yoshida Brewery last year. He underwent training in Dewazakura Brewery in Yamagata Prefecture, and began working at his family’s brewery 10 years ago. He is also the master brewer of Yoshida Brewery.

They have traditionally used the Yamada-nishiki and Gohyakumangoku brewers’ rices, and have also used Ishikawa Prefecture’s original Ishikawamon since 2008 and Hyakumangoku-no-Shiro since 2018. Brewers’ rice is easily damaged when ground, and each brand shows different characteristics in taste and aroma produced through fermentation and tolerance against bacteria. Mr. Yoshida explained the characteristics, likening the brands to students in a school class.

“Yamada-nishiki is like a superstar. He is ranked first in study and sports, physically perfect and popular among classmates. Gohyakumangoku is also ranked highly for study, yet he is not good at all subjects. For example, in PE he can run fast but cannot play ball games well. However, he can be an excellent supporter; if Yamada-nishiki was class president, Gohyakumangoku might be a good vice president. In fact, Gohyakumangoku works very well when used as malt rice. Ishikawamon is easily damaged when ground and contaminated by bacteria, producing a smoky aroma, which is disapproved of in sake brewing. It is like a difficult child who is poor at both study and exercise yet gifted at art and music. It can change dramatically depending on how it is dealt with. Hyakumangoku-no-Shiro might be like a student who has newly transferred to the school. He surprises his classmates with his ability in study and sports yet still remains mysterious. Every child has his own good point and I love everyone.”

Mr. Yoshida said the taste of sake produced all around the country had improved during the last ten years, but he was not completely happy with the brewing conditions. Such conditions include refrigeration technologies used in the processes from brewing to distribution, the use of additives to facilitate fermentation, and technologies to change water quality to facilitate fermentation. Thus, there are many brewing methods that require a large amount of energy and deny the traditional brewing skills that have been created locally. If we give an extreme example, it is possible to produce quality sake even in a building in the center of Tokyo if we obtain excellent brewer’s rice from somewhere, adjust the water quality and use the advanced technologies and abundant electric power. However, does such sake have value as a local product? What characteristics should we value and what should we change? As a local brewery, Yoshida Brewery pursues desirable methods while returning to their roots from time to time.

“Water is our foundation. The wild Tedori River carried mountain rocks to this plain, and the groundwater here is medium-hard, containing many minerals. The conservation of healthy forests and rice fields is indispensable in preserving this water quality. We felt a sense of crisis when rice fields began to be replaced with factories and shopping malls, so we began to actively use local rice seven years ago. Hyakumangoku-no-Shiro is suited to the climate of this region; therefore, it is ideal from the perspective of sustainability. Now that we have brewed sake from Hyakumangoku-no-Shiro three times, we understand its strong compatibility with the local water and traditional brewing methods that we cherish. We’d like to produce next-generation sake using the brewing skills unique to this area, and the water and rice that can only be obtained here.

The true merit of Hyakumangoku-no-Shiro, the mysterious transfer student, will be tested from here onward.

Yoshida Brewery

Yasuyoshimachi, Hakusan, Ishikawa

Telephone: 076-276-3311

https://tedorigawa.com/

Photographs:SHINJO ARAI

Text:KOH WATANABE

(supported by Ishikawa Prefecture, Ishikawa agriculture total support organization)